King Kalākaua's "Secret" Society

Originally Appearing in "Hawaii Intrigue" (Abstract 4)

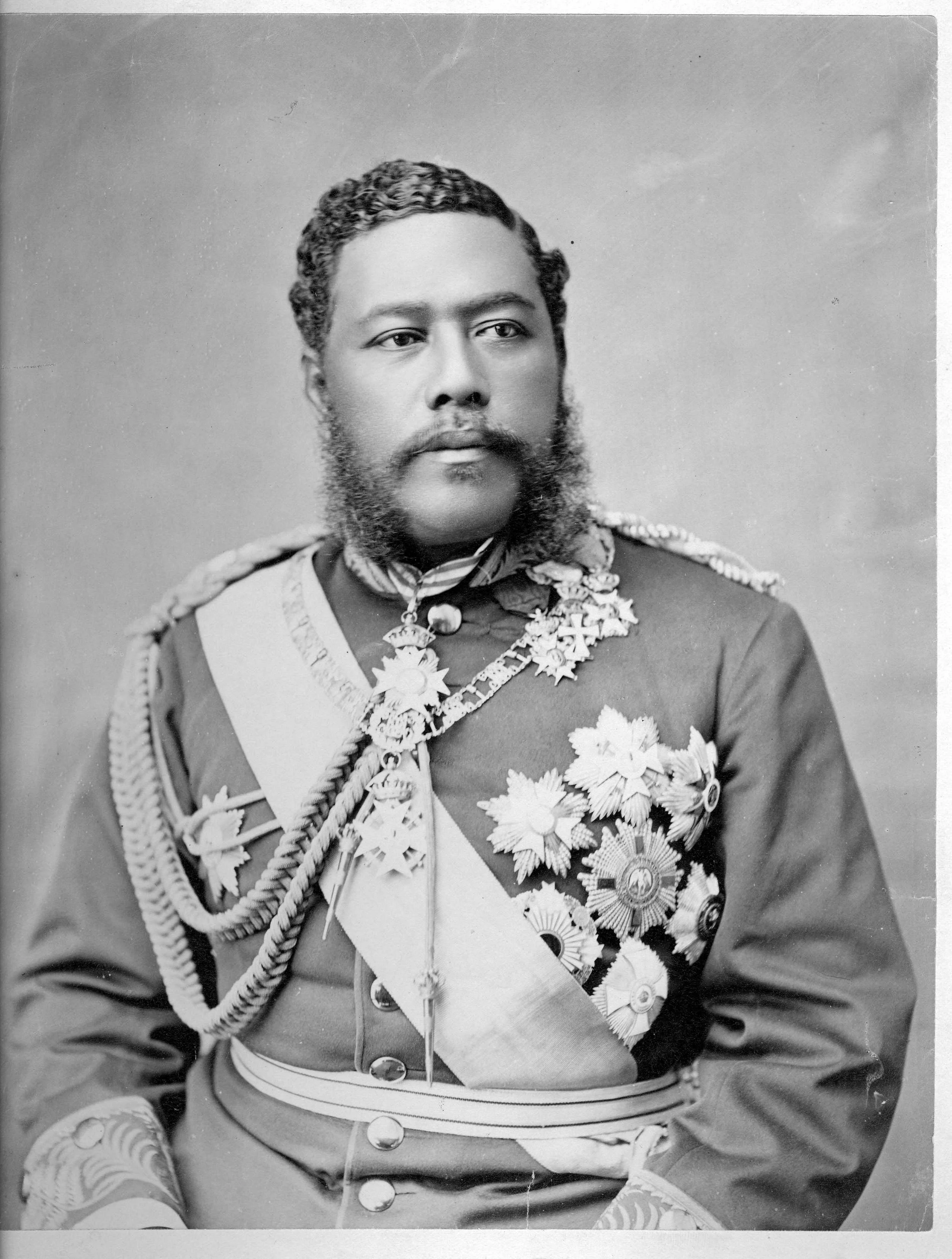

Words by Jason K. Ellinwood // Image by J. J. Williams, Hawai'i State Archives Collections

While the Freemasons are often spoken of today in conspiracy theories that link them to the Illuminati, this "secret" society had an active and visible role in 19th century Honolulu, with a prominent membership that included three kings: Kamehameha IV, Kamehameha V and Kalākaua. Kalākaua, though, wanted to create a uniquely Hawaiian society, so he founded Hale Nauā in 1886.

Hale Nauā, given the English names "House of Wisdom” and "Temple of Science," was dedicated to preserving traditional Hawaiian knowledge, while also seeking connections to modern Western science. Unlike the fraternal organizations imported from the West, both women and men were welcome to join Hale Nauā, although membership was limited to those of Hawaiian ancestry. Perhaps it was this genealogical requirement that caused the Missionary Party (descendants of American missionaries who had grown wealthy with the rise of the sugar industry) to oppose Hale Nauā, accusing the society of promoting paganism and lewd practices. This was one of the many critiques leveled at Kalākaua by this group of white businessmen who felt that their voice in government was not proportional to the taxes they paid. In 1887 they forced Kalākaua to sign what became known as the Bayonet Constitution, which disenfranchised Asian immigrants and poor Hawaiians and diminished the power of the monarchy.

Despite the accusations of clandestine immorality, Hale Nauā operated with a remarkable amount of transparency for a "secret" society. An article that appeared in the Nov. 15, 1890 issue of the Hawaiian-language newspaper Ka Nupepa Elele gave details about the finances of the organization, as well as describing current projects, such as a Hawaiian calendar. The article also reported that all members of Hale Nauā received "Crosses of Honor" from a "Renowned French Scientific Society."

With the death of Kalākaua in 1891, Hale Nauā ceased to be active but continued to be attacked by members of the Missionary Party. In the years following their overthrow of Queen Liliʻuokalani in 1893, the rulers of the "Republic of Hawaiʻi" attempted to sway American public opinion in favor of annexation and the supposed paganism of Hale Nauā was used as a justification of their actions. Evidence of their influence is found in an article, printed in Ke Aloha Aina on Dec. 14, 1895, about a Baptist minister in New York sermonizing about "pagan" Hawaiians, with the "worst of the paganism" being Kalākaua's activities with Hale Nauā.

Supporters of the monarchy replied in an editorial in the Dec. 16, 1895 issue of Ka Makaainana that, "These missionary descendants who have grown fat off of Hawaiʻi are shameless in spreading falsehoods such as this [...] This society [Hale Nauā] was no different from the other secret societies of the foreigners." Despite these rebuttals and other efforts by the royalists, the Missionary Party was ultimately successful in their goal of annexation. However, the legacy of King Kalākaua and Hale Nauā survives to this day in the form of the traditional Hawaiian knowledge that they helped to preserve.